The Hungarian Media Authority favoured its own ranks when deciding who could report illegal content to online platforms

It raises questions about conflict of interest that Hungary’s Media Authority appointed its own legal aid service as a trusted flagger. This is the task the Trump administration calls censorship.

The Digital Services Act (DSA) came back into the spotlight again at the end of last year when the European Commission used it to penalize X, Elon Musk's platform. Shortly thereafter, the US government decided to introduce travel bans against five European citizens fighting disinformation, including some who had previously worked on the DSA.

Among those banned are the leaders of a German organization called HateAid. According to the US State Department, the problem with this organization is that it is considered a "trusted flagger" under the DSA legal framework, meaning it can play a prominent role in notifying online platforms when it finds illegal content on their sites. In the US government's interpretation, this is equivalent to censorship.

While looking into the system of trusted flaggers, we came across something interesting.

This is interesting because the NMHH itself is the so-called "digital services coordinator" in the framework of the DSA. This means that

Although the NMHH did not break any explicit rules, this raises concerns about conflicts of interest, as the Internet Hotline and the NMHH are in a hierarchical relationship: the Internet Hotline has been operated by the NMHH since 2011, from the same headquarters as the authority. In its response to Lakmusz, the Media Authority emphasized that the tasks are separate, but according to the law and the NMHH's organizational regulations that a hierarchical relationship indeed exists.

Previously, MEPs also questioned the independence of the NMHH in a letter to the European Commission.

In our article, we explain the tasks of the digital services coordinator and the trusted flagger, and we also look at what the problem might be with the designation of the Internet Hotline with the help of Máté Szabó, director of programs at the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU).

Trusted flagger and the coordinator

These two entities play a role in the DSA legal framework, specifically in the regulation of platforms such as Facebook or X. Under the DSA, trusted flaggers are special organizations that are considered experts in "detecting certain types of illegal online content, such as hate speech or terrorist content, and reporting it to online platforms."

Trusted flaggers are responsible for "detecting potentially illegal content and alerting online platforms," meaning they send notifications to platform operators when they detect such content. Any user can do this, but the difference is that platforms must treat reports made by trusted flaggers as a priority and decide on them “without undue delay.”

Such designated trusted flaggers are appointed by the digital services coordinator of the country concerned, who is the organization responsible for everything "related to the application and enforcement of the DSA." So, they act as a kind of professional DSA officer, monitoring platform providers operating in the country and checking that they comply with the rules laid down by the DSA. In Hungary, this role has been performed by the NMHH since January 1, 2023.

It is not surprising that the national media authority was appointed as coordinator in Hungary, as this was also the case in many other EU member states. However, the fact that the legal aid service operated by the NMHH became the trusted flagger, raises questions.

Meets the criteria, yet it's odd

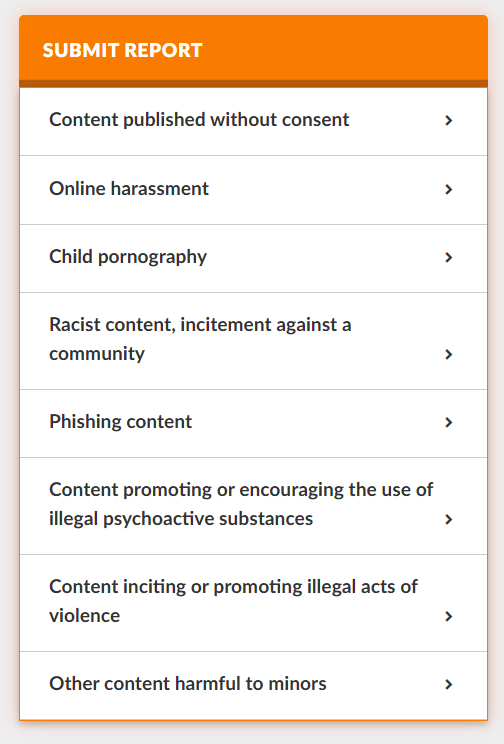

On October 25, 2024, the NMHH designated the Internet Hotline as the trusted flagger in Hungary. The Internet Hotline is a legal aid service maintained by the NMHH, where reports can be filed about online content that is suspected of being illegal or harmful, in eight different categories, such as online harassment, child pornography, racist, inflammatory, or phishing content.

To become a trusted flagger, an organization must be based in the EU and meet the following criteria:

- expertise and competence: trusted flaggers must have experience and expertise in identifying and reporting illegal online content;

- independence: the organization must be independent of any platform provider;

- accuracy and objectivity: the organization must act accurately, objectively, and impartially in accordance with established rules.

These conditions are also set out in the NMHH's 2024 resolution.

The text of the DSA provides some guidance on what types of organizations can be trusted flaggers:

- public authorities, such as national law enforcement agencies,

- non-governmental organizations, private organizations, or semi-public organizations, such as organizations dealing with reports of racist and xenophobic content, or legal aid services that belong to the INHOPE network.

The INHOPE network is an association of hotlines for reporting child sexual abuse material, which Internet Hotline joined in 2012.

If we look at the list of trusted flaggers, we see that the picture is indeed mixed: the list includes organizations dealing with copyright protection, media awareness, addiction, Holocaust remembrance, social welfare, child protection, legal aid services, and even fact-checking organizations. These include both civil society and public institutions. Many countries have multiple trusted flaggers, such as Austria, France, Finland, and Romania.

Interestingly, the Irish Media Council, which acts as Ireland's digital services coordinator, published a handbook on trusted flaggers in February 2024. This handbook also discusses (Annex 2, page 8) how the Council interprets the concept of a trusted flagger under the DSA and concludes that while authorities can act as flaggers, digital services coordinators cannot.

Conflict of interest

Máté Szabó, director of programs at the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, told Lakmusz that he could not think of any example of a coordinator appointing an organization that it itself operated as a trusted flagger. "This is not standard practice at all," said Szabó, adding:

"What the NMHH did in this case does not formally conflict with the provisions of the DSA. Rather, it raises questions of conflict of interest and independence: the coordinator checks whether the trusted flagger meets the conditions set out in the DSA, the trusted flagger also submits its annual report to the coordinator, and the coordinator can also revoke the trusted flagger's mandate. In theory, these should be separate institutional functions, but it is questionable to what extent the NMHH is able to enforce them effectively and credibly vis-à-vis a trusted flagger which is within its own organization.”

We asked the NMHH how they guarantee the independent operation of the coordinator and the trusted flagger. In its response, the Media Authority wrote that, according to the 2010 Media Act, the NMHH has "three bodies with independent powers: the President, the Media Council, and the Office, whose powers, areas of operation, and activities are clearly and unambiguously defined by law." The NMHH noted that the operation of the legal aid service is the responsibility of the Office, over which "the President has no authority to issue instructions regarding its professional management." The role of digital services coordinator is performed by the President. In other words, according to the NMHH, the two roles are separate:

"The President, who exercises the powers related to the digital services coordinator, and the Internet Hotline operated by the Office as a trusted flagger, perform their activities independently of each other."

According to the NMHH's organizational and operational rules, the legal aid service is operated by the NMHH Internet Hotline Department. This body is indeed under the direct control of the Director General, who heads the NMHH Office.

However, both the NMHH's rules of procedure and the 2010 Media Act (Section 111, 2/d) clearly state that:

"The President appoints the Director General of the Office and exercises employer's rights over him or her, including dismissal and recall."

Máté Szabó said that the DSA does not stipulate that the trusted flagger must be a civil society organization, but in his opinion, the investigation and control of illegal content appearing on platforms can become politically sensitive at any time, so it is good practice if this task is not assigned exclusively to one authority. A good example of this is when several trusted flaggers are appointed in a country, including civil society organizations, so that experts in different fields, state and civil society organizations can complement each other's work.

"The independence of the NMHH is questionable anyway, and the appointment of the coordinator was in itself a politically controversial decision," says Máté Szabó. This is also demonstrated by the fact that in February 2024, 36 MEPs wrote a letter to EU Commissioners Margrethe Vestager and Thierry Breton expressing their concern that Hungary had appointed as coordinator the NMHH, which, according to the MEPs, "is known for its links to government propaganda, and thus may violate the DSA's independence requirements."

Máté Szabó stressed that:

"It is important to emphasize that this is a criticism of the structure and not of the operation of the Internet Hotline, as we have little insight into that."

Actions following the Internet Hotline’s reports

As a trusted flagger, the Internet Hotline is required to publish an annual report. According to the 2024 report (that, since the Internet Hotline became a trusted flagger on October 25, 2024, the 2024 report covers only two months):

In most cases, the Internet Hotline reported content published without consent (43 percent) or phishing content (37 percent) to platform providers. In addition, there was also content inciting violence or illegal acts, child pornography, and online harassment.

At the end of the report, they also note that their work is completely independent of platform providers.

Their report for the full year 2025 has not yet been published, as the deadline for submission is March 2026. However, at the end of October last year, Internet Hotline published a summary of their past year, in which they describe how service providers are responding more quickly and effectively to reports, citing Google, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Discord, and Telegram as examples. In the latter case, they also note that while in 2024 they reported 39 cases of illegal content spreading on Telegram, in 2025 they reported 57 cases. In most cases successfully, as they got feedback from the platform. However, we will only see accurate data when last year's report is made public.

Cover photo: András Koltay, President of the Media Authority, by Noémi Bruzák/MTI

Follow us

Follow HDMO on our social channels to stay up to date with our latest news.